When we fight for change, there are opportunities inside the system, as well as tried and true methods outside of it. We’ve talked this week about how Blacks fought and won for the right to vote. We’ve also discussed using protest to disrupt the system and to call attention to the systemic injustices that Blacks encounter.

What happens in the space and time between these two ventures? What happens when we bring revolution to the institution? Today’s post is about how we work in and for an institution that won’t have us, how we maneuver in a political system that would rather use us than do the right thing, and how we effect change in a world that would rather we go quietly to our lonely sunken places.

First, let’s talk about how the American political system has interacted with its Black constituents. Let’s look at the historical context of the two major Parties.

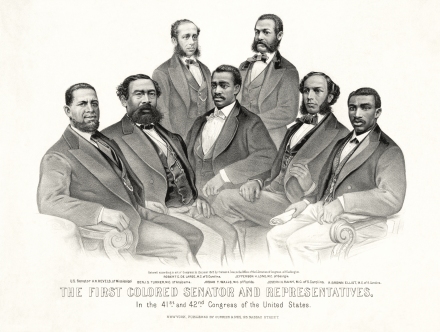

The Republican Party in the time of Abraham Lincoln is well known for amending the constitution to officially end institutionalized enslavement and the Civil War. During Reconstruction and the early 20th century, they welcomed Blacks into its ranks, with the first Congressional representation of Blacks taking seats less than a month after the passage of the 15th Amendment, which gave Black men the right to vote. On the other hand, Democrats focused their efforts on representing the Southern white agrarian, who now had lost their principal livelihood — slavery — and additionally had to begin to compete with the freed labor of Blacks. To attempt to wrest political power from their opponents, Democrats appealed to the fears of whites, enflaming and encouraging conflict. This, in turn, gave them impetus and cover to disenfranchise Blacks from the political process. Southern Democrats used legal tactics like White Primaries, in which only whites were allowed to vote, and establishing hurdles to voting like literacy tests and the poll tax (Jim Crow Laws). They also collaborated with terrorist organizations, like the Ku Klux Klan, who exacted violence and employed intimidation tactics against Blacks and white Republican voters. These strategies established the Solid South as an anti-Black Democratic political stronghold for nearly a century.

A transition was initiated with Roosevelt’s Depression-era New Deal: feeling (disproportionately) the economic collapse, Blacks hoped that a rising tide would raise all ships — Whites and their own — so they saw intimations of allyship within the Democratic Party. With the Democrats approach to economic problems, their priorities and bases of support realigned, and they emerged as a more liberal Party with stronger roots in the labor movement. Republicans became the home of the Anti-New Deal, pro-business conservatives, as well as of moderate New Deal-positive liberals.

Then, in the 1960’s Democratic Presidents supported more changes that brought increased equality to racial minorities, like the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was signed into law by Lyndon Johnson. The Senate approved across a mix of geographical and party lines. However, the general result was that Republicans became the new home of anti-Black politics: One of the most virulent white supremacists in 20th Century congressional history, Strom Thurmond was a Democrat, but switched parties in 1964 to become a Republican.

This shift was solidified during the presidential candidacy of Republican Barry Goldwater, who opposed the Civil Rights Act on constitutional grounds. When he assured whites that the states should implement the law in their own time, it was a message (to both whites and Blacks) that there would be continued to resistance to equality. Having won over a new white constituency for the Republican Party, this was the birth of the Southern Strategy. Since then, the Republicans have been the Party with the loudest dog whistle (e.g., buying into Birtherism) and the Party that seeks to leverage the manufactured conflict between Blacks and socio-economically disadvantaged whites. Since the late 1960’s, the Republicans have not been a friend to Blacks. They have moved rightward toward fascism, and today, if someone wants to run as a member of the KKK, a Neo-Nazi, or just a White Supremacist, this is the Party where they are currently welcome, whether it be through active encouragement or tacit endorsement.

After the shift in the 1970’s, Democrats typically carry over 90% of the Black vote. But, let’s be clear, Democrats are not saviors either. Bill Clinton’s commitment to the poorly conceived and malevolently implemented Drug War through his 1994 crime bill set the stage for the modern era of mass incarceration, which highly disproportionately traps Blacks in generational cycles of poverty. Also, neoliberalism, which emphasize the health of capitalistic systems over human welfare and social progress, has become a significant driver of Party policy. Beyond this, many still demonstrate ignorance and insensitivity, and often, out-right anti-Blackness. For example, in the 2017 Georgia special election for Senate, the campaign of candidate Doug Jones used Blacks as his primary voting block – while his campaign used them as props in a racist ad. Also, the Party continues to focus on the economic challenges of the white working class, centering Whiteness and dangling the carrot of representation in front Black voters. The relationship between Democrats and Blacks is shaky, because we know when we’re getting played.

When there is no place for you, you make your own. Bridging the space between community-based organizations and the mainstream of electoral politics, new groups arose out of the forge of the Civil Rights Movement. The most famous of these groups, the Black Panther Party, was founded in 1966 in Oakland by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. The group represented a radical, revolutionary departure from white normative society, emphasizing self-determination and full liberation for Black people everywhere. The Panthers’ Ten Point Program spelled out the party’s demands plainly:

What We Want

What We Want

-

-

- We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black community.

- We want full employment for our people.

- We want an end to the robbery by the White man of our Black community.

- We want decent housing, fit for shelter [of] human beings.

- We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

- We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

- We want an immediate end to police brutality and murder of Black people.

- We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county, and city prisons and jails.

- We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black communities. As defined by the constitution of the United States.

- We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

-

The Black Panthers’ philosophy was a sophisticated amalgam of Marxist philosophy and the existing Black power movement of the time. Black Panther actions cleverly worked within the rule of law to critique the law itself, and drawn attention to its failure to serve Black people: their first actions were the use of armed patrols for the protection of their communities in Oakland (the original name of the party was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, and was later shortened). Founders Bobby Seale and Huey Newton studied California’s open carry law in impeccable detail, and took advantage of their legal right to openly carry firearms in establishing arms patrols. These patrols began in Oakland, but then spread to Richmond CA (in response to the killing of a Black youth by police there) and beyond as the party grew in subsequent years. In arming themselves, the Black Panthers were essentially demonstrating their belief in the sovereignty of Black communities, and the presence of police as an occupying force. When California State attempted to do away with open carry, the Black Panthers made national news by entering a State Assembly Chamber while armed, thus bringing themselves to national attention. Chapters sprung up around the country following the media coverage of the event.

In the years immediately following their founding, the Black Panther Party went through a variety of changes: they founded a number of free community programs, such as the Free Breakfast for Children program, along with community healthcare, and other essential services. Again, the presence and success of these programs in serving their communities was a stark reminder of the government’s failure to address these same needs.

While in their earliest years the party emphasized Black masculinity as its basis, leader Huey Newton soon denounced sexism as anti-revolutionary, and Black women rose to positions of leadership. The Black Panthers adopted a Womanist stance, centering the intersecting experiences of race, class, and gender in the lives of Black women, over mere feminism, a “theoretical paradigm that addresses the observations of middle-class White women”. Women within the Black Panther began a program of Child Care to the Party, providing free collective childcare that allowed women to participate fully in both family life and party leadership and/or actions.

Despite the “party” in their name, the Black Panthers did not largely pursue positions in elected government, with the exception of Bobby Seale running for Oakland mayor in 1972, and Elaine Brown (who subsequently became head of the party) running for Oakland city council in 1973. However, a number of former Black Panthers have eventually crossed that bridge into traditional government structure and sought elected office (for example, Representative Bobby Rush of Illinois’ 1st District, who since 1992 has represented a district covering much of Chicago’s South Side. Until redistricting in 2013, his district had the highest proportion of Black residents in the country). See here for more info/reference.

Across the waters in South Africa, the Black Panthers were influencing the thinking of those who were part of The Struggle against Apartheid (pronounced “apart”+”hate”, and meaning “separateness” in Afrikaans). Bantu Stephen Biko was a South African Freedom Fighter and the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa. While Apartheid had many opposers, Steve Biko became frustrated with how the anti-Apartheid struggle had become the fight of white liberals, so even the struggle against an oppressor became separate from a celebration of Blackness, of identity. Biko was involved in the National Union of South African Students, who opposed Apartheid but “reflected the opinions of the majority of its members who were white”, as Donald Woods recalled in his biography, Biko. The book is enlightening about Biko’s personal journey – and it’s publication in 1987 also resulted in the exile of Woods himself. Here’s a short clip of Cry Freedom, a movie based on the Woods biography.

As he wrote when defining the Black Consciousness in 1971:

What Black Consciousness seeks to do is to produce real black people who do not regard themselves as appendages to white society. We do not need to apologise for this because it is true that the white systems have produced through the world a number of people who are not aware that they too are people.

There were many players in The Struggle who fought either in South Africa or in exile to end Apartheid. Often we remember leaders who celebrated peace and unity, particularly as people continue to try and build a New South Africa. While peace is an incredibly important ideal and our process of reconciliation is lauded around the world, we can remember how people like Nelson Mandela (whose vision of creating a unified society healed the South African nation) were also standing on the shoulders of men and women like Steve Biko who fought for not only a principled struggle, but a fight that included them as Black people as the focus. We should think about this as people who care about fighting racism and white supremacy. How much of my efforts conspire to removing Black voices? How can I leverage my voice to highlight others? Part of his challenge was to redefine the fight, redefine the narrative from within a well-established struggle:

“It becomes more necessary to see the truth as it is if you realize that the only vehicle for change are these people who have lost their personality.”

After being arrested in 1977, Steve Biko was interrogated for 22 hours, and was beaten by at least one of ten police officers who were present. He died of extensive brain injury while in custody on the 12th of September 1977. He was one of 46 political detainees to die from 1963 – 1977 since the South African government passed laws allowing imprisonment without trial in 1963, for those suspected of terror against the state. Detention without trial is practiced in the USA today for those suspected of terrorism.

I just wish to have that unity back that we once had

LikeLike